Robots Are Moving Into Factories — So Why Are Some Plants Hiring More People?

Every time somebody says “robots are taking our jobs,” I picture a Roomba rolling into HR and asking for a W-2. Funny image… but the real story is messier (and honestly, more interesting) than the doomsday headline.

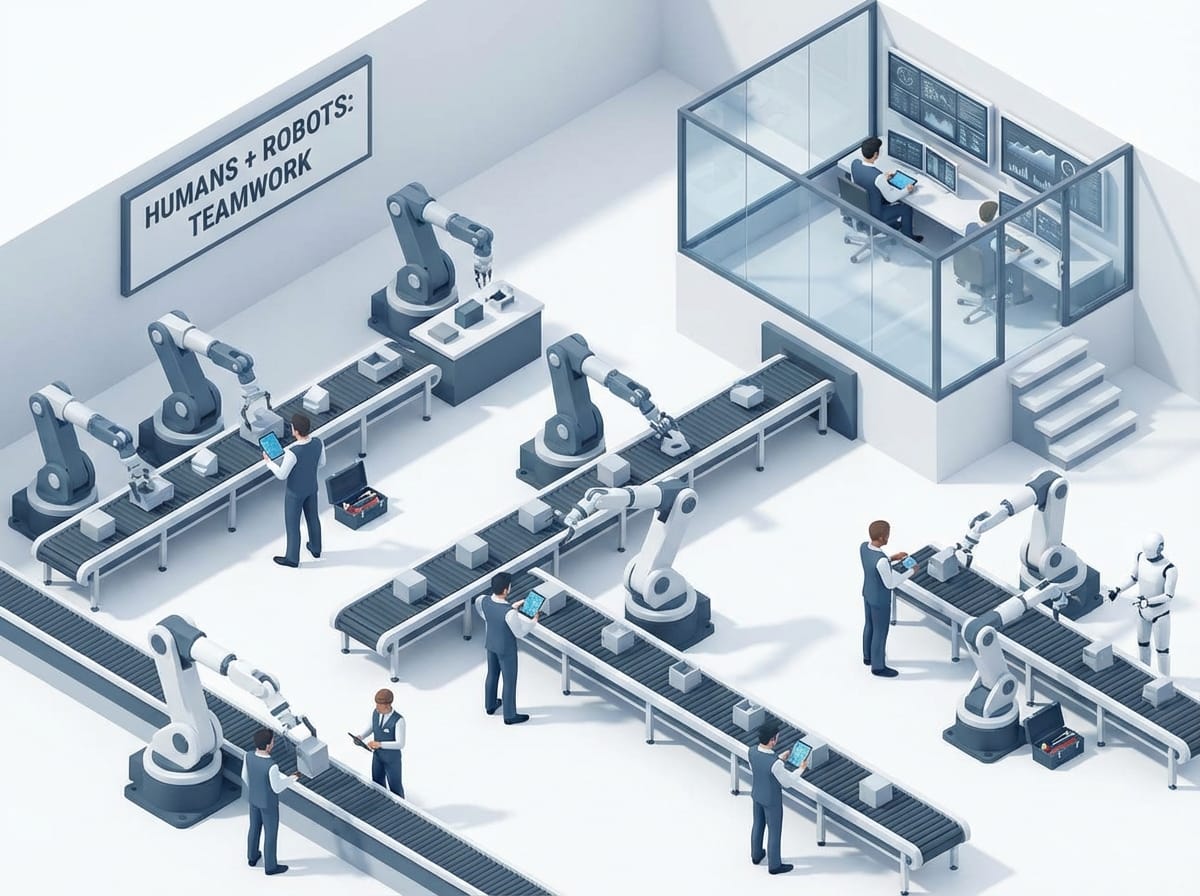

Yes, robots do replace certain tasks. Some roles shrink. Some disappear. But here’s the twist a lot of people miss: in a bunch of real factories, robots have shown up… and headcount still went up.

So what’s actually happening? Let’s talk about what the data says, why it looks contradictory, and what you (or your company) should do about it.

Robots in factories: job killer or job creator?

My take: robots are neither heroes nor villains. They’re power tools. A forklift “eliminated” a lot of backbreaking lifting work too, but it also created warehouse jobs, logistics jobs, safety training jobs, maintenance jobs—you get the idea.

Recent research looking at U.S. manufacturing plants from 2010–2022 found something that surprises people: plants that adopted robots increased both production and employment [1]. Production rose more than employment (hello, productivity), but employment still rose across all skill levels—production and support functions included [1].

And it’s not just abstract math. One example from the same research: a General Electric plant in Norwich, New York advertised 169 job openings between 2014 and 2022 even after adopting robots [1]. That’s not exactly “lights-out factory, nobody left.”

Why robots can increase jobs inside the same plant

Let’s break this down like we’re explaining it to a smart friend over coffee. Robots change work through three main mechanisms:

1) Substitution: robots take tasks, not “people”

Robots are great at repetitive, precision-heavy, and hazardous tasks. If you’re doing the same weld 10,000 times a week, robots are coming for that task. That can reduce demand for certain routine roles.

But it’s rarely the whole job. A welder doesn’t just weld—there’s setup, inspection, rework, coordination, safety, troubleshooting. Automation tends to eat the most repetitive slice first.

2) Complementarity: robots create “robot-adjacent” work

Robots don’t magically appear, plug themselves in, and start performing like they’re in a Pixar movie. Somebody has to:

- spec and purchase the equipment

- design the cell and workflow

- install and integrate it

- program and reprogram it

- maintain it and keep uptime high

- supervise quality and safety

That’s complementarity—new work that exists because the robot exists. Research explicitly calls out these roles: design, installation, programming, maintenance, and supervision—engineers, technicians, and operators [1].

Here’s the part people overlook: job postings increased across all occupations, including ones you’d assume would get crushed by automation like welders and painters [1]. Translation: even “automation-exposed” roles can stay in demand when production scales and the factory gets busier.

3) Productivity gains: more output can mean more hiring

This is the “bigger pie” effect. If robots raise output and reduce defects, the plant can sell more. More sales can mean more shifts, more packaging, more shipping, more procurement, more customer support, more supervisors—the whole ecosystem.

In other words, robots can lower the cost per unit enough that the company wins more business. Then they need more humans to handle everything the robot doesn’t do (which is… a lot).

Okay Marty, so why do we still see layoffs?

Because zooming out from “a plant” to “the whole economy” is where it gets spicy.

Globally, one common estimate says automation could eliminate 75 million jobs while creating 133 million new ones [2]. That sounds optimistic—until you remember the fine print: the new jobs aren’t always in the same place, at the same time, for the same people.

Also, the “robots in factories” story is now colliding with “AI in offices.” That’s a different wave, and it’s accelerating budget decisions.

Venture capital investors expect that by 2026, companies will redirect budgets from labor toward AI and automation—potentially accelerating layoffs [3]. I read that as: even if the long-term job picture is net-positive, the short-term transitions might be rough, especially for roles that are easy to automate and hard to redeploy quickly.

And displacement isn’t evenly distributed. One study found employment in AI-vulnerable occupations is 3.6% lower in regions with high demand for AI skills after five years [5]. So geography matters. Industry mix matters. Local training capacity matters. (A fancy robot doesn’t help if there’s nobody around who can keep it running.)

The real bottleneck isn’t robots. It’s skills speed.

In my opinion, the biggest risk here isn’t “robots replacing humans.” It’s “humans not getting re-skilled fast enough to work alongside the robots.”

There are some encouraging signs: vocational program enrollment and apprenticeship investment are rising [4]. But the broader labor signals are weird: the college wage premium has been flat since 2010, and salaries for knowledge jobs plateaued since mid-2024 [4]. That suggests we’re in a world where “just get a degree” isn’t the cheat code it used to be, and companies are still figuring out what to pay for what skills.

So the challenge is timing: can we retrain and redeploy workers into these new robot-adjacent roles before the old tasks get automated away?

What jobs grow when robots show up?

If you’re trying to future-proof a career (or a workforce plan), I’d bet on roles that sit close to the automation but aren’t easily automated themselves:

- Automation/robotics technicians (keeping machines alive is a full-time job)

- Controls engineers (PLCs, sensors, industrial networking)

- Quality and metrology (inspection, measurement systems, root-cause analysis)

- Industrial maintenance (mechanical + electrical + software is the new trifecta)

- Production supervisors and line leads (humans coordinating humans + machines)

- Safety and compliance (robots don’t remove risk; they change it)

And yes, plenty of “classic” manufacturing roles still matter—especially when demand rises and plants run more shifts. The work shifts from pure manual repetition to setup, monitoring, exception-handling, and problem-solving.

Practical advice (because vibes don’t pay bills)

If you work in manufacturing

- Get closer to the machine. Volunteer for automation projects. Ask to shadow maintenance. Learn how the line actually works.

- Pick one technical “spine.” PLC basics, industrial electricity, CAD, QA methods—just choose one and go deep.

- Document your impact. “Reduced downtime 12%” beats “helped with robots.” Always.

If you run a plant or lead operations

- Budget for training like you budget for equipment. Buying robots without upskilling is like buying a jet and skipping pilot school.

- Design career ladders. Operator → cell tech → automation tech is a real pathway if you build it.

- Measure productivity <em>and</em> churn. If automation boosts output but spikes attrition, you’ve got a hidden cost.

If you’re a policymaker or educator (or just a concerned citizen)

- Speed matters. Short, stackable credentials can beat four-year programs for fast transitions.

- Train where jobs are. Regional differences are real [5]. Funding should follow local industry demand.

So… are robots taking jobs?

They’re taking tasks. They’re shifting demand. They’re forcing uncomfortable change. But inside many robot-adopting factories, the evidence says employment can rise alongside output [1]. That’s not a guarantee everywhere—some regions and roles will get hit harder [5]—but it’s a strong rebuttal to the simplistic “robots = fewer jobs” narrative.

The winning move is to treat automation like electricity: it doesn’t replace the business, it rewires it. The people who learn to work with it don’t get replaced—they get promoted.

Actionable takeaways

- If you’re worried about robots, get robot-adjacent. Maintenance, controls, quality, safety, and supervision are durable lanes.

- If you’re deploying automation, invest in humans. Training isn’t optional; it’s part of the capex.

- Expect uneven outcomes. Industry and geography matter, and transitions can be bumpy even when the long-term picture is positive.

Sources: [1] Research on U.S. manufacturing plants adopting robots (2010–2022), summarized in provided research data; [2] World Economic Forum, The Future of Jobs (job displacement/creation estimates); [3] Investor expectations on 2026 resource allocation shifts toward AI/automation, summarized in provided research data; [4] Workforce training/apprenticeships and wage trend notes, summarized in provided research data; [5] Regional employment impacts in AI-vulnerable occupations (3.6% lower after five years in high AI-skill-demand regions), summarized in provided research data.